|

| A mortality compost pile with the media bed where the animal was placed and cover material on top. (Photo Credit: Melissa Wilson/University of Minnesota Extension) |

Composting is a widespread practice for many types of organic materials that can be adapted to handle livestock mortalities. While many of the aspects and processes in mortality composting echo composting other organics, one key difference is how time factors into an efficient and successful process.

In a mass mortality situation, we need a quick solution to safely handle a lot of carcasses. Once mortality composting is started, the human time commitment is relatively low - but one does need to be prepared for how long the compost pile will be in place. The Minnesota Board of Animal Health can be consulted to determine if and when composting is the appropriate solution for your situation.

Time Considerations

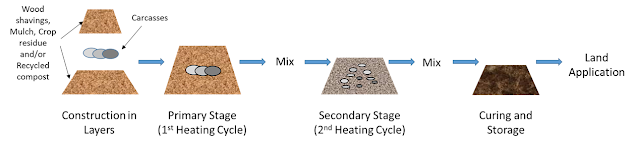

Composting, by definition, is the conversion of organic material to carbon dioxide, water, and heat through aerobic (oxygen-aided) processes. With mortality composting, there are several stages to complete this process.- The primary stage (1st heat cycle) is for the breakdown of soft tissue and softening of bones.

- The secondary stage (2nd heat cycle) furthers the breakdown process.

- The curing process finishes the breakdown process at lower temperatures.

Two heat cycles are necessary. Monitoring the internal temperature of the pile with a temperature probe is the suggested method for tracking the composting process, to make sure the 130°F temperature is reached and maintained for 7 to 10 days in each of the primary and secondary stages. Sufficient temperature rise and then cooling to ambient air conditions is a good indicator for the end of the primary and secondary stages. Mixing after the first and second stages rejuvenates the composting process by redistributing nutrients, moisture, and air through the pile.

The primary and secondary stage time depends on the mass of the largest intact carcass, as well as weather conditions and management. Opening a carcass can speed up the process. The below chart shows some approximate timelines to be aware of.

| Consider the largest, intact animal size | Primary Stage Time | Secondary Stage Time | Curing | Total Time |

| Beef cow (~ 1500 lbs) | 90 - 180 days | 60 days | 30 days | 6 - 9 months |

| Sow (~ 500 lbs) | 60 - 120 days | 40 days | 30 days | 4 - 6 months |

| Finishing Pig (~300 lbs) | 45 - 90 days | 30 days | 30 days | 3 - 5 months |

| Nursery Pig (~ 50 lbs) | 20 - 35 days | 12 days | 30 days | 2 - 3 months |

| Anything 3 lbs or smaller | 10 days minimum | 10 days | 30 days | 2 months |

- Is the location accessible and available for the required total time?

- How many other farm operations need to shift because of the compost pile, size, and/or location?

- Will the sight of the compost pile in this location be an unwelcome reminder of a challenging time?

Other considerations for mortality composting

Besides time and patience, the key resources for mortality composting include the carbon amendment and other cover material, a water source, equipment, and space. Operators will need appropriate equipment, such as a front-end loader, for mixing the piles as well.- Supporting material: A mortality composting pile has two parts when it is initially set up: the media bed, on which the carcass material is placed, and the cover material. The material for the media bed and cover material is a source of carbon for the composting microbes, which should retain moisture and porosity. Mulch, wood shavings, and crop residue are popular options. Sometimes a mixture of sources works best for the media bed, to achieve some moisture-holding capacity. For example, while straw and corn stalks are great carbon sources with high porosity, the surface of the straw and corn stover tends to shed water. Chopping and mixing either of these with some compost, or sawdust, provides a good mixture of both moisture and porosity. The cover material serves as an additional odor barrier. Water-shedding material may be a better option for the surface of the mortality pile, to reduce precipitation entry into the pile. The Minnesota Board of Animal Health provides a list of contacts for carbon sources.

- Water Source: Composting is efficient and effective when the moisture content is around 50%. The compost material should leave your hand feeling moist, but you should not be able to squeeze any water out of it. For a mass mortality pile, consider ways to add moisture if rainfall is not sufficient. Options may include a water truck or soaker hose.

- Equipment: The right equipment makes any job easier. A loader will aid in pile construction and will also be needed for turning and mixing the pile after the primary and secondary stages.

- Space: The rule of thumb is that 3 to 5 yards of media accompany 1000 pounds of animal mass. Always check with local and state rules on whether there are restrictions on where composting occurs relative to groundwater or other water sources. Equipment accessibility and maneuverability around the site and pile, water availability, and visibility are other factors.

Resources for setting up mortality composting

- MN Composting Animal Mortality Guide - https://datcp.wi.gov/Documents/minnesotacompostguide.pdf

- USDA Livestock Mortality Composting Protocol - https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergency_management/downloads/nahems_guidelines/livestock-mortality-compost-sop.pdf

Additional resources

- MN Board of Animal Health Emergency carcass disposal resources during COVID-19 - https://www.bah.state.mn.us/emergency-carcass-resources/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery#emergency-carcass-disposal-resources-during-covid-19

- MN Pollution Control Agency Guidelines for Livestock Carcass Disposal - https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/wq-f6-07b.pdf

- USDA-NRCS Emergency Milk Disposal and Emergency Animal Mortality Management - https://unl.app.box.com/s/sbjlc11xo3fvuqlre1z6a2gux8lft8vn

- USDA-NRCS Funding available to help with emergency livestock mortality - https://www.bah.state.mn.us/media/EQIP-Livestock-Mortality-Initiative-fact-sheet-4_2020.pdf

For the latest nutrient management information, subscribe to Minnesota Crop News email alerts, like UMN Extension Nutrient Management on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, and visit our website.

Support for Minnesota Crop News nutrient management blog posts is provided in part by the Agricultural Fertilizer Research & Education Council (AFREC).

Comments

Post a Comment